This may take up to thirty seconds.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Passover is a celebration and honor of rebirth. We remember the survival and resilience of our ancestors, who fought for our freedoms and life. We recall as well as our own rebirth as we navigate life, shedding our past selves that no longer serve us and embrace the experiences and challenges that give birth to us again and again. We also bear witness to the rebirth of our natural environments, remembering that ever-moving cycles are our constant tethers and after long periods of stillness can emerge beauty.

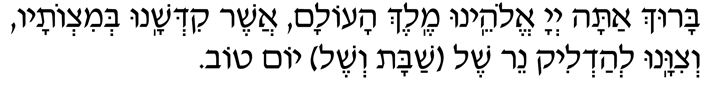

We light candles to remember and to designate holy spaces. We distinguish this moment of sacredness from our daily lives. We also look to light as a symbol of justice and truth, to kindle these flames within us, and to share out light with others.

Baruch atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, asher kid'shanu b'mitzvotav v'tzivanu l'hadlik ner shel Yom Tov.

Blessed are You, our God, Spirit of the world, who sanctifies us with mitzvot and calls upon us to kindle the lights of the Festival day.

Let us all fill our glasses with wine!

Spring is the season of new growth and new life. Every living thing must either grow, or die; growth is a sign and a condition of life. Like no other creature, the most significant growth for a human being takes place inwardly. We grow as we achieve new insights, new knowledge, new goals. Let us raise our cups to signify our gratitude for life, and for the joy of knowing inner growth, which gives human life its meaning. And with raised cups, together let us say:

בְּרוּכָה אַתְּ יָהּ אֱלֹהֵינוּ רוּחַ הָעוֹלָם בּוֹרֵאת פְּרִי הַגָפֶן

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה אֲדֹנָי אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, שֶׁהֶחֱיָנוּ וְקִיְּמָנוּ וְהִגִּיעָנוּ לַזְּמָן הַזֶּה

Baruch atah Adonai, eloheinu melech ha'olam, borei pri hagafen.

Baruch atah Adonai, eloheinu melech ha'olam, shehechiyanu v'kimanu v'higi'anu lazman hazeh

Blessed are you, God, Spirit of the universe: who creates the fruit of the vine;

Blessed are you God, Spirit of the universe, who has kept us alive, sustained us, and brought us to this season.

We will wash our hands twice during our seder: now, with no blessing, to get us ready for the rituals to come; and then again later, we’ll wash again with a blessing, preparing us for the meal.

Too often during our daily lives we don’t stop and take the moment to prepare for whatever it is we’re about to do. Let's pause as we wash our hands to consider what we hope to get out of our time together.

Passover, like many of our holidays, combines the celebration of an event from our Jewish memory with a recognition of the cycles of nature. As we remember the liberation from Egypt, we also recognize the stirrings of spring and rebirth happening in the world around us. The symbols on our table bring together elements of both kinds of celebration.

We now take a vegetable, representing our joy at the dawning of spring after our long, cold winter, and dip it into salt water, a symbol of the tears our ancestors shed as slaves. Before we eat it, we recite a short blessing:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ, אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה

Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech ha-olam, borei p’ree ha-adama.

We praise God, Ruler of Everything, who creates the fruits of the earth.

We look forward to spring and the reawakening of flowers and greenery. They haven’t been lost, just buried beneath the snow, getting ready for reappearance just when we most needed them.

By Ada Limón

More than the fuchsia funnels breaking out

of the crabapple tree, more than the neighbor’s

almost obscene display of cherry limbs shoving

their cotton candy-colored blossoms to the slate

sky of Spring rains, it’s the greening of the trees

that really gets to me. When all the shock of white

and taffy, the world’s baubles and trinkets, leave

the pavement strewn with the confetti of aftermath,

the leaves come. Patient, plodding, a green skin

growing over whatever winter did to us, a return

to the strange idea of continuous living despite

the mess of us, the hurt, the empty. Fine then,

I’ll take it, the tree seems to say, a new slick leaf

unfurling like a fist to an open palm, I’ll take it all.

There are three pieces of matzah stacked on the table. We now break the middle matzo into two pieces. One piece is called the Afikomen, literally “dessert” in Greek. The Afikomen is hidden and must be found before the Seder can be finished.

We recognize that liberation is made by imperfect people, broken, fragmented — so don’t wait until you are totally pure, holy, spiritually centered, and psychologically healthy to get involved in tikkun (the healing and repair of the world). It will be imperfect people, wounded healers, who do the healing as we simultaneously work on ourselves.

We eat matzah in memory of the quick flight of our ancestors from Egypt. As slaves, they had faced many false starts before finally being let go. So when the word of their freedom came, they took whatever dough they had and ran before it had the chance to rise, leaving it looking something like matzo.

Uncover and hold up the three pieces of matzah and say together: This is the bread of poverty which our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt. All who are hungry, come and eat; all who are needy, come and celebrate Passover with us. This year we are here; next year we will be in person. This year we are slaves; next year we will be free.

Reader 1: Long ago, there was a king named Pharaoh, who ruled the land of Egypt. The Hebrew people who lived in Egypt were Pharaoh’s slaves. Pharaoh was worried that a Jew might grow up to be a leader of the Hebrew slaves, and fight against him. So, Pharaoh ordered that all little Jewish boy babies were to be killed. He told the midwives, women who helped babies to be born, to kill the Hebrew babies. The midwives loved all babies, so they refused to obey his orders. Two midwives, Shifrah and Pu’ah, told Pharaoh lies to protect the little babies. One Jewish mother, named Yocheved, was very worried about her new baby boy, and she put him in a basket and set the basket on the river. When Pharaoh’s daughter went down to the Nile to bathe, she saw the basket among the reeds. She opened it, saw the baby was crying, and felt sorry for him. Pharoah's daughter named him Moses, saying, “I drew him out of the water.”

Reader 2: Moses’ sister, Miriam, watched Pharaoh's daughter take the baby out of the water, and told her, “I know a woman who can help you take care of your baby.” Miriam ran home, and brought back her Mom, Moses’ birth mother. The Princess asked Yocheved to help her take care of the baby, not knowing who she was. Yocheved agreed. We can imagine Miriam giggling happily, knowing her baby brother was alive, free, and safe with his adopted mother and his birth mother. As he grew, Moses watched the Jewish slaves working hard for Pharaoh. One day, he saw a Hebrew slave being badly beaten by an Egyptian guard, so Moses killed the guard. He knew Pharoah would be very angry at him, so he left Egypt and became a shepherd in a far-away place. There, he married a woman named Tzipporah, the daughter of the priest of Midian, and they started their own family.

Reader 3: One day, Moses saw a burning bush. When he got closer to it, he heard a voice coming from it. It was the voice of God.God called to Moses from within the bush and said, “I have seen the misery of my people in the Narrow Places. I have come down to rescue them and to bring them up into a land flowing with milk and honey. I am sending you to Pharaoh to bring my people, the Israelites, out of there.” Moses said to God, “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and bring the Israelites out of the Narrow Places?” And God said, “I will be with you.” Then Moses said to God, “So I go to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your ancestors has sent me to you,’ and they ask, ‘What's his name?’ What shall I tell them?” And God said, “ I am who I am. This is what you are to say to the Israelites: I am has sent me to you.’” Moses knew that it was wrong that the Jewish people were slaves. He felt in his heart that they were his own people, just as God told him. Some people believe Moses really heard the voice of God, just like we hear our friends or our parents talking to us. Other people believe that the voice Moses heard was his own small voice coming from within his heart. It told him something wasn’t right, and he should try to fix it. The voice within his heart told him that all people are part of the human family, and that all people should be treated kindly and fairly.

Reader 4: Moses went back to Egypt, just as God told him to do, with his birth brother, Aaron. He went to the new Pharaoh, and said, “Let my people go!” Pharaoh refused. Moses warned Pharaoh that if he didn’t let the Jewish slaves go free, bad things might happen to him. According to Jewish tradition, God was punishing Pharaoh. Others believe the plagues were all scientifically explainable coincidences. God gave Pharaoh a chance to change his mind, and to let the Jewish people go free. Although Moses pleaded with Pharaoh to give in, the most terrible punishment of all came to Pharaoh. The first-born child in each family died. The Jewish families painted a mark on their door with lamb’s blood, so that the last curse would “pass over” their homes. Pharaoh’s own son died, and this time he said, “Go!”

Reader 5: Moses was relieved that Pharaoh finally said the Hebrew slaves were free to leave, but he was worried that Pharaoh would change his mind. He told the slaves to hurry and to follow him. They didn’t have time to bake bread to eat on their trip, so they put raw dough on their backs. It baked into hard crackers just like the matzah you see on the table. The Jewish people followed Moses until they arrived at the sea. Pharaoh had changed his mind and his army was following them. Moses put his walking stick in the sea, and the water miraculously moved to make a path for them to walk through. Before Pharaoh’s army could cross the sea, the water returned to normal.

Reader 6: When the Jewish people reached the desert on the other side of the sea, they started a new life. Miriam, Moses’ sister, led the women in a freedom celebration of singing and dancing. Moses told the Jews to tell their children and their grandchildren the story of how they became free. We are those grandchildren, and this is our story. That is why we still celebrate Passover today.

The telling of the story of Passover is framed as a discussion with questions and answers. The tradition that the youngest person asks the questions reflects the idea of involving everyone at the Seder.

מַה נִּשְּׁתַּנָה הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה מִכָּל הַלֵּילוֹת

Ma nishtana halaila hazeh mikol haleilot?

Why is this night different from all other nights?

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹת אָנוּ אוֹכְלִין חָמֵץ וּמַצָּה, הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה - כּוּלוֹ מַצָּה

1) Shebichol haleilot anu ochlin chameitz u-matzah. Halaila hazeh kulo matzah.

Why is it that on all other nights during the year we eat either bread or matzo, but on this night we eat only matzo?

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹת אָנוּ אוֹכְלִין שְׁאָר יְרָקוֹת, - הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה מָרוֹר

2) Shebichol haleilot anu ochlin shi’ar yirakot haleila hazeh maror.

Why is it that on all other nights we eat all kinds of herbs, but on this night we eat only bitter herbs?

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹת אֵין אֶנוּ מַטְבִּילִין אֲפִילוּ פַּעַם אֶחָת, - הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה שְׁתֵּי פְעָמִים

3) Shebichol haleilot ain anu matbilin afilu pa-am echat. Halaila hazeh shtei fi-amim.

Why is it that on all other nights we do not dip our herbs even once, but on this night we dip them twice?

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹת אָנוּ אוֹכְלִין בֵּין יוֹשְׁבִין וּבֵין מְסֻבִּין, - הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה כֻּלָנו מְסֻ

4) Shebichol haleilot anu ochlin bein yoshvin uvein m’subin. Halaila hazeh kulanu m’subin.

Why is it that on all other nights we eat either sitting or reclining, but on this night we eat in a reclining position?

Reader 1: It is customary to speak of four different types of children who may be present at a Seder: the wicked or rebellious child, the wise child, the simple child, and the child that doesn't know how to ask. Today we look within ourselves and notice four different child-like parts within us all. We can think of them as parts of our “innerchild”.

Reader 2: Our Independent inner-child wants Biblical stories to be relevant, spiritual, uplifting and personal. This part will not settle for easy answers, leaps of faith, or a lack of depth. We remind this inner-child that we are connected to all who came before us. We have an obligation to hear their story.

Reader 3: The Wise inner-child in us appreciates the traditions which have been passed generation to generation for thousands of years. This part wants to know why we do what we do, and how our traditions have emerged. We teach this inner-child about our heritage and encourage them to add the newest chapter to our great story.

Reader 4: The Non-verbal inner-child wants learning to be lively and fun, not just reading from a book. They want us all to connect emotionally and spiritually. We offer this inner-child food and song, love and family.

Reader 5: The Simple inner-child in each of us wants to hear the story a-new, as if we had never heard it before, with the wide-eyed wonder of a young child. As we share our story, we interact with it in a way that makes the story fresh and new each and every me. Each time we tell it, it is as if we are there again.

As we rejoice at our deliverance from slavery, we acknowledge that our freedom was hard-earned. We regret that our freedom came at the cost of the Egyptians’ suffering, for we are all human beings made in the image of God. We pour out a drop of wine for each of the plagues as we recite them.

Dip a finger or a spoon into your wine glass for a drop for each plague.

These are the ten plagues which God brought down on the Egyptians:

Blood | dam | דָּם

Frogs | tzfardeiya | צְפַרְדֵּֽעַ

Lice | kinim | כִּנִּים

Beasts | arov | עָרוֹב

Cattle disease | dever | דֶּֽבֶר

Boils | sh’chin | שְׁחִין

Hail | barad | בָּרָד

Locusts | arbeh | אַרְבֶּה

Darkness | choshech | חֹֽשֶׁךְ

Death of the Firstborn | makat b’chorot | מַכַּת בְּכוֹרוֹת

The passover story acts as a framework for other injustices in our world. Just as we were enslaved in Egypt, there are other people today who are still suffering from oppression. As we overcame our bondage, we hope that everyone suffering will soon be free.

Lets acknowledge some modern plagues of today:

Homelessness and poverty

Inequality

Greed

Discrimination and hatred

Silence and violence

Envionmental destruction

Stigma of mental illness

Xenophobia and racism

Sexism and transphobia

Mass Incarceration

(Feel free to add any others not listed)

Refill your cup, it's time for the second glass!

At the seder we say/sing that: If we had been brought out of Egypt, Dayenu. If we had received Torah, Dayenu.

Dayenu means “it would have been enough.” Dayenu is a song all about appreciating what we have, what we’ve been given, and what we've fought for. Think of dayenu as a template for gratitude. How many times do we forget to pause and notice that where we are is exactly where we ought to be? Dayenu is a reminder to never forget all the miracles in our lives. When we stand and wait impatiently for the next one to appear, we are missing the whole point of life. Instead, we can actively seek a new reason to be grateful, a reason to say “Dayenu.”

But think, too, about how actually it is to be enough to be satisfied when there is still suffering and oppression. Some say “lo dayenu,” meaning, “it is not enough.” When we are free and others are not, lo dayenu. We work to find the balance between being grateful for what is right with our lives and with the world, and also striving for more that fulfills us and more that increases justice in the world. Dayenu is a call to collective action. A call to join together to fight for justice. We continue to fight until we are freed from the deepest roots of our chains.

Join in song:

CHORUS: .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Da-ye-nu, da-ye-nu, da-ye-nu!

Ilu na-tan, na-tan la-nu, Na-tan la-nu et-ha-Sha-bat, Na-tan la-nu et-ha-Sha-bat, Da-ye-nu!

If he had given us Shabbat it would have been enough!

CHORUS: .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Da-ye-nu, da-ye-nu, da-ye-nu!

Ilu na-tan, na-tan la-nu, Na-tan la-nu et-ha-To-rah, Na-tan la-nu et-ha-To-rah, Da-ye-nu!

If he had given us the Torah it would have been enough!

CHORUS: .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Da-ye-nu, da-ye-nu, da-ye-nu!

.. .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Dai, da-ye-nu, .. Da-ye-nu, da-ye-nu!

At this point in the Seder we get ready to eat and wash hands again, this time saying a blessing. Ritual washing has long been a part of Jewish tradition, and also a part of our daily lives, especially salient during this pandemic. We wash to protect ourselves and to eliminate the spread. As we wash, let us be grateful for our access to clean, potable water, and make the commitment to ensure clean, safe water for everyone everywhere. Water is a human right- from Flint, Michigan to Palestine, from the droughts in California to Israel, we remember that without water we cannot survive. It is our duty to protect the sources of water in our communities from pollution and environmental degradation, as well as fight for water access in our country and world.

Pour cup of water over one hand three times then the other; pat dry with a nice towel. We recite:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יי אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, אֲשֶׁר קִדְשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו וְצִוָּנוּ עַל נְטִילַת יָדַיִם

Baruch atah Adonai, melech/ruach ha'olam, asher kidshanu b'mitzvotav v'tzivanu al netilat yadai'im

Blessed are you, God, ruler of the universe, who makes us holy with good rules such as washing our hands.

The bitter herbs serve to remind us of how the Egyptians embittered the lives of the Israelites in servitude. When we eat the bitter herbs, we share in that bitterness of oppression. We must remember that slavery still exists all across the globe. When you go to the grocery store, where does your food come from? Who picked the sugar cane for your cookie, or the coffee bean for your morning coffee? We are reminded that people still face the bitterness of oppression, in many forms.

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ, אֱלֹהֵֽינוּ מֶֽלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָֽׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו וְצִוָּֽנוּ עַל אֲכִילַת מרוֹר

Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech ha-olam, asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu al achilat maror.

We praise God, Ruler of Everything, who made us holy through obligations, commanding us to eat bitter herbs.

The egg (flower for vegans) reminds us of spring, when plants are growing and baby animals are being born. Eggs have been symbols of life’s renewal in many faiths throughout history. The egg is a symbol of our potential in life – as individuals, as families, and as communities and nations. Flowers represent our blossoming and blooming as people as we go through new stages in life. Just as an egg needs warmth and love and security to hatch and flowers need care and tending, we need all of these things to grow as well. With love and care between people, we are each more likely to reach our potential.

The bone/beetroot reminds us of the first celebration of Passover, when Jewish families roasted a lamb and ate it with matzah. The blood of the lamb was used to put on the doors of the Jewish slaves’ homes so that punishments intended for Pharaoh would “pass over”.

A recent addition to the seder plate is an orange, to honor women and LGBTQ+ people in Judaism. In the 1970’s, the first women were ordained as Rabbis. According to one story, during a speech by a Jewish scholar Dr. Susannah Heschel, a man in the audience yelled out, “a woman belongs on the bimah as much as an orange belongs on the Seder plate!” A new tradition was born. As we share the orange pieces, we honor the religious and spiritual contributions of women and LGBTQ+ people in the Jewish community and throughout all of time.

The olives represent an olive branch- a symbol of peace between people. May there be peace between all peoples on Earth and may we do our part to take steps towards peace. This includes Jewish values of accepting and loving the stranger, making new people feel comfortable, learning about other traditions and cultures with an open mind, calling out racism, sexism, and xenophobia, and making sure everyone feels included.

Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.

Time for children (of all ages) to find and eat the Afikomen - remembering to balance the serious memories of slavery with the joyfulness of freedom.

Finish cup two, we're about to refill!

The third cup of wine is the cup of freedom.

Now is the time to take another drink of wine to remind us to take responsibility for the oppression that occurs around us, just as Moses, Miriam and the midwives did. We remember that freedom is something we must work for, for ourselves and for others.

Reader 1: The story has been told of a miraculous well of living water which had accompanied the Jewish people since the world was spoken into being. The well comes and goes, as it is needed, and as we remember, forget, and remember again how to call it to us. In the time of the exodus from Mitzrayim, the well came to Miriam, in honor of her courage and action, and stayed with the Jews as they wandered the desert. Upon Miriam’s death, the well again disappeared.

Reader 2: We use the cup as a feminist symbol of the importance of women, who are often overlooked in our traditional texts, but were integral to the survival of our people- both in the desert and throughout history. Also, water is a life-sustaining force and a human right. It is an important environmental justice symbol as all humans deserve access to clean water. It can also symbolize sustenance in general- what are things that give us life and sustain us? Whether its food, water, shelter, or our relationships to others, education, etc. Think about the things in life that sustain you through times of hardship.

Reader 3: “Zot Kos Miryam, kos mayim hayim. Zeikher l’yitziat Mitztrayim.

This is the Cup of Miriam, the cup of living waters. Let us remember the Exodus from Egypt. These are the living waters, God’s gift to Miriam, which gave new life to Israel as we struggled with ourselves in the wilderness. Blessed are You God, Who brings us from the narrows into the wilderness, sustains us with endless possibilities, and enables us to reach a new place.”