This may take up to thirty seconds.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/a-seat-at-my-seder-table/

A seat at my seder table

Add these women’s perspectives -- diverse in affiliation, background, and more -- to your discussions on leaving Egypt and feel more like you were there

I am the oldest child in my family and — with age — I have become more comfortable admitting that I was a pretty competitive sibling. The Passover seder table, in particular, was a forum for showing off how much I knew about the holiday and obnoxiously showing up my younger sisters. My parents encouraged us all to ask questions and to answer as much Passover trivia they could throw at us. I obviously took on that challenge. Along with others like, who could drink the most grape juice? Who finished all their matza? Who could stay awake the longest? It was a perfect platform for my competitive nature and I apologize now for reinforcing the message of bitterness a little too well for my sisters. It is actually quite impressive that they still invite me over for the holiday.

I hope I have since tempered my behavior, but one childhood rule from our family seder still remains integral to my seder participation. My father demanded that every seder participant come to the table with a dvar Torah, a reflection or teaching related to the Passover holiday — and it had to be something new each year. No repeats. As a child, I (obviously) took that assignment pretty seriously. I would bring my school notebook to the table or scan the children’s haggadah for a “new and novel” tidbit to impress my family. I am still grateful for this family tradition, because it ensured that each seder conversation was new and different from year to year — because of my own contributions and the shared contributions of others around the table. It also made the seder experience feel “different from all other nights” — I had to come prepared to contribute to the conversation and elevate it for everyone.

There have been years when I made the time to delve into some Passover learning and came to the seder table laden with highlighted texts and source sheets. There have been other years when I could only manage to cobble together a semi-provocative question relating the Exodus story to a current event. But my “M.O.” of late has been to print out an assortment of online Passover wisdom shared by others and then read them over in time for the second seder (one advantage of having a second chance at seder execution!) and share something that resonated with me.

This Passover will be no different. Except.

Last week, we launched a new venture with SVIVAH called “HerTorah” — a space dedicated to women’s perspectives on Torah under the direction of Aliza Sperling, in partnership with Maharat and the Aviv Foundation. We invited Rachel Sharansky Danziger to share her thoughts on cultural storytelling and let the women in the room examine the methods they use to share their important life stories. Rachel focused on the central storytelling tactic of the haggadah where we are supposed to remember the story of the Exodus as if we ourselves experienced it – in the first person. “Bechol dor vador chayav adam lir’ot et atzmo ke’ilu hu yatza mi’Mitzrayim” — In every generation, each person is obligated to relate to the Exodus as if it been their own personal journey. In our planning for HerTorah, we invited the Jewish Women’s Archive to talk about their work preserving and amplifying the stories and perspectives of Jewish women. JWA’s executive director, Judith Rosenbaum, gave a moving talk highlighting how the stories of women are foundational to our Judaism, but how they are often overlooked. It is a powerful reminder that so much of our cultural history is lost when we forget to include the voices of our women. JWA thoughtfully sent along some of their “women’s stories” related to Passover to share at our gathering — and that was the moment it clicked for me.

Aliza Sperling. April 2019. (courtesy)

I decided to pass on my family tradition to the women of SVIVAH. This event was all about preparing for the seder discussion and also telling the stories of women. So I started printing. I started printing seder stories and perspectives told in women’s voices. This is not new or novel — women’s Torah scholarship is something we can thankfully take for granted. But when I focused on that storytelling strategy of “first person experience of the Exodus,” I realized how important it was to bring more women to my seder table. If I wanted to experience the story of leaving Egypt as if I was there myself, I should bring voices to the table that sound similar to mine.

So I collected the voices of women.

And it is really nice that these are all voices of women — not that some of them couldn’t have been written by men, but it is nice to be able to note that these are all women’s voices being invited to contribute to my seder stream of consciousness. There are many different types of readers, but when I read, I try to hear the voice of the writer in my head. Since many of the scholarly writings selected were written by pillars of our local DC Jewish community — as I read, these really are voices I can hear in my head. I have had the privilege to hear many of them speak and teach, so in reading their thoughts about Passover, I really can hear them. I can really feel their presence at my seder table. With the obligation of the seder to have everyone imagining themselves as if they, too, left Egypt, it was notable to surround myself with commentary about that journey in a voice that sounds similar to my own, from voices that I know and respect.

We shared Sixth & I’s, Rabbi Shira Stutman, “Relying on Miracles” and Erica Brown’s “Dayenu: A Jewish Template for Gratitude” and “The Ten-Second Seder.” There was Esther Goldenberg’s “Omer Journey” and Rabbi Sarah Tasman’s “Passover Yoga: Meditation & Creative Expression,” with At the Well, and Rabbi Nina Beth Cardin on “The Deepest Meaning of Hineini.” From the executive track of Maharat, local Alana Suskin shared her thoughts on “Pesach: A Radical Freedom.”

Since Rachel Sharansky Danziger presented us with a literary analysis of the haggadah, we wanted to include other literary perspectives on the story of the Exodus. Of course, we wanted more Rachel Danziger, with her “Memories of the Exodus: The First Going Out”, but also the in-depth On Being interview with Dr. Avivah Zornberg, “The Transformation of Pharaoh, Moses, and God.” Some literary creativity with author Ilana Kurshan and her “Exodus Sonnets,” as well as Gail Reimer’s “Passover Poetry: Re-Telling the Story of Our Own Lives” and author Tova Mirvis, with her timely piece for the Jewish Women’s Archive: “Passover in Charleston.” And someone shared this beautifully illustrated Charlotte von Rothschild Haggadah (1842), the only Hebrew manuscript known to have been illuminated by a woman.

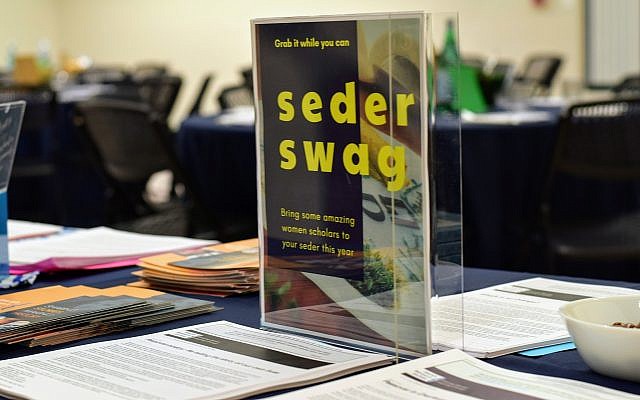

We wanted women to find voices that sounded like their own, but also voices that they would be open to hearing. A diversity of women’s perspectives — in affiliation, background, generation, identity — it made the table feel heavy with richness. Rabbi Dr. Erin Leib Smokler shared her Pastoral Torah from Maharat on “Ze Eli V’Anvehu: Pointing to a Personal God.” Women’s oppression through the timely lens of #MeToo was a critical component, through Rabbi Tamara R. Cohen’s piece on “Passover, #MeToo, and a Mirror on the Seder Plate.” We offered the Maharat Pesach Companion and the Hadar Haggadah. Rabbi Avital Hochstein presented thoughts “On Belonging and Otherness.” Addressing feminism head-on were Sharon Weiss-Greenberg and her “Four Questions Every Feminist Should Ask Herself at the Passover Seder” and “What’s in an Orange?” by Jordan Namerow. It was inspiring to see women of all ages and affiliations work their way around the “SVIVAH Seder Swag” table, comparing selections, making recommendations to women they were only first meeting. They were sharing their stories, voices they were familiar with. Perspectives were shared, lenses were broadened, women’s stories were told.

Joy Ladin wrote of “Passover: Festival of Binaries” for Keshet. IKAR’s Rabbi Sharon Brous shared “We Are an Exodus People,” alongside Rabbi Sari Laufer’s “The Oft-Misquoted Catchphrase of the Exodus.” Rabbi Jill Hammer’s “On Passover Remembering Our Oppression with Sweetness” brought the Shekhinah into the mix. From Hadar, Rabbi Avi Killip offered “Stories and Redemption,” while Dena Weiss shared “Four Different Questions.” And — because I let my own story be part of the table — I added Mayyim Hayyim’s guide to immersing “In Preparation for Passover,” and “Bridges and Puzzles: Understanding the Haggadah” from Sefaria director and childhood friend, Sara Wolkenfeld. This collection is a thoughtfully random assortment. There are hundreds more women’s voices who should also be invited to the table. As you can see, this is not Torah about women. This is simply women’s perspectives on Torah. I find myself asking every woman I cross — whose voice would you want to invite to the table?

When we were developing the concept of HerTorah, we asked one of SVIVAH’s senior consulting educators if she thought there was educational value in creating a women*-only space for Jewish study. Without missing a beat, she responded, “Without a doubt. There have been many times I’ve taught the same exact curriculum to a room of men, a mixed-gendered room, and a room of women. The input — my curriculum — is exactly the same. The output in each room? Vastly different. Each audience will have a different outcome. Now, one is no more valuable than the other. In fact, it is fitting with the concept of ‘there are 70 different faces of the Torah.’ A room of women will uncover one of those faces. And a full understanding of our texts will be incomplete without it. So is there value? It’s imperative.” In other words, we cannot expect to fully understand our foundational stories without the perspective of women.

This HerTorah gathering was a space dedicated to women’s voices and perspectives. It was not crafted with the same intention as a “women’s seder,” but more to affirm that the method in which we tell our stories as women is foundational to our faith tradition. HerTorah was born of the need to reinforce the foundational importance of the perspective of women. It is about creating a space for us to sit together and share our stories, so we can use our collective experience to discover and unearth this version of our faith foundation. The story angle that lets us see ourselves in it more clearly. The story told in voices that sound similar to our own.

So I collected a selection of diverse, multigenerational women’s perspectives on Passover. I pulled out a few chairs and invited these women scholars to join me at my seder table. And I hope that in surrounding myself with the voices of women, I can more clearly envision my own Exodus, the path and the journey I would have taken out of Egypt, as if I had been there myself.

—

—

*SVIVAH defines a “Jewish woman” as anyone wishing to join a circle of Jewish women. www.svivah.org

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Ariele Mortkowitz is passionate about the ways women interact with their faith and their community and has dedicated herself to the pursuit of fulfilling Jewish spiritual and communal experiences for women. She founded SVIVAH, a venture dedicated to nourishing women’s communal faith experience -- inspiring, supporting, connecting, and celebrating Jewish womanhood. As a volunteer mikvah guide for over 15 years, Ariele saw how ritual could augment an individual’s spiritual journey and create a space for personal connections, leading her to create the Agam Center, an expansion of what a mikvah can be to a community. She earned a Certificate in Spiritual Entrepreneurship through the Clal Glean program and Columbia Business School. She is also a YCT/Maharat/JOFA-certified premarital teacher. Originally from New Jersey, Ariele currently lives in Washington DC with her family.

For so many of us, the Seder is a ritual to ‘get through.’ There is someone rushing through the words, another person checking the clock, another drooling over the smells from the kitchen. What if as the seder unfolds, we knew we could look forward to an opportunity for pause and reflection? Using the prompts below, transform your seder table into a circle of balance.

Note: These exercises can either make up a complete ‘mindfulness seder’, or you can choose one or more to incorporate into a seder you are leading or attending.

Kadeish קדש – recital of Kiddush blessing and drinking of the first cup of wine

As you begin the seder, there is often a great deal of anticipation. Looking forward to that first sip of wine, taste of matza, warm soup…instead of counting how many pages to the next section, focus in on each step of this ritual. One method is to narrate (either out loud or in your mind) each step as objectively as possible: “I am holding the glass. I am opening the wine. I am pouring the wine. I am holding up the glass. [say blessing] I am sipping the wine. I am swallowing the wine.” Notice what arises in this practice - is it calm and presence, or more agitation or anticipation? Bonus: try it for each of the 4 cups and see how it changes.

Urchatz ורחץ – the washing of the hands

Water is life and our hands are purified by the waters. Instead of washing and then rushing to dry them off, hold your wet hands open on your lap or on the edge of the table. Sit in silence or quiet whispers as you watch and feel the water evaporating. Take bets on when they will be fully dry or have a contest who can go the longest without drying them on the closest napkin.

Karpas כרפס – dipping of the karpas in salt water

Reciting blessings over our food is a chance to slow down and connect to the source of our nourishment. Assemble platters of three or more vegetables for each guest, or invite each guest to assemble mini platters at their seat after passing around a tray of vegetables. Choosing one item at a time, hold it in the air with your focus on the vegetable. What’s did it look like while in the ground? (You may wish to provide photos - I’m especially fond of photos of potato plants!) Close your eyes and imagine the trip from the ground to the store to your plate. Then say the blessing.

Yachatz יחץ – breaking the middle matza

The breaking of the matza should be done in silence. As you prepare for the break, count three long breaths with eyes open and focus on the matza, held high for all to see. Listen closely to the sound of the matza breaking. At this moment, we hold the paradox of wholeness and brokenness; the matza is both the bread of our affliction and the bread of freedom. Take three more deep breaths. Optional: Share with someone next to you or the whole table - what paradoxes in your life are you sitting with today?

Maggid מגיד – retelling the Passover story, including the recital of "the four questions" and drinking of the second cup of wine

Dayeinu: What in our lives do we take for granted, but may actually be enough for us? Share with someone next to you or the entire table. After each person shares, respond: Dayeinu!

Rachtzah רחצה – second washing of the hands

So much of the seder is talking and listening. Finally, here’s a part that has almost no talking. After you say the hand washing blessing, choose a niggun (simple wordless melody) that you and your guests can carry until everyone has finished washing. Use eye contact and the raising of the matza for motzi to signal the end of the blessing.

Motzi Matza מוציא מצה – blessing before eating matzo

The first bit of matza is always the driest. One is truly meant to savor that bite and not mix with any other dips or spreads. As you begin to munch on the first bit, notice what thoughts, feelings, and sensations arise. Joy, dryness, satiation...what else? Allow these to come and go without judgement until your serving of matza is consumed.

Maror מרור – eating of the maror

The embodied practice of purposely consuming maror has deep symbolism. Dipping ¾ ounces of maror into charoset, which is sweet, brings healing and alignment as we approach the formal meal.

Koreich כורך – eating of a sandwich made of matzah and maror

Koreich is a memory sandwich. Since we no longer slaughter a lamb for the paschal sacrifice, there is only maror on our matzo sandwich. Though the pesach sacrifice is primarily represented with the zroa, shankbone, on the seder plate, our memory sandwich is the key moment of the seder to recall this sacrifice. Though we do not recite an additional blessing for this sandwich, as we chew, we recline and recall the communal rite of the shared roasted lamb.

The moment we consume this sandwich, we are simultaneous recalling the Pesach offering, both from Temple times and from our last night in Egypt. What makes this symbol so powerful is that we have the capacity to recall two moments in history simultaneously:

The word “Pesach” is literally the name of this sacrifice, which was done in memory of the one performed in Egypt on the night of the 10th plague when they put animal blood on the doorposts The Torah commandment to consume the offering on the Passover holiday comes from Exodus 12:8: “They shall eat the flesh that same night; they shall eat it roasted over the fire, with unleavened bread and with bitter herbs.” and then in verse 14: “This day shall be to you one of remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a festival…” (See Exodus 12:3-14 for the full section).

In Temple times, there were many key rituals regarding a sacrificed lamb or goat shared amongst family. In Exodus 12:3 we read “שֶׂ֥ה לַבָּֽיִת - a lamb per household.” One could not observe this ritual one their own - usually, families would combine with neighbors to afford a high quality lamb to share on the holiday.

Shulchan oreich שלחן עורך – lit. "set table"—the serving of the holiday meal

Many seder meals begin with a spherical object, such as an egg, gefilte fish, or matza ball. Take a moment to examine this round food item, with no beginning and no ending. You have made it to the midpoint of the seder; and yet, this round item reminds us there is no beginning and no end. We are fully redeemed and we are still waiting to be redeemed. Turn over the item again, then bring it to your mouth for the first bite.

Tzafun צפון – eating of the afikoman

Walking meditation: And opportunity to get out our seats and wander. Perform the search in silence. Take your steps slowly and carefully. Extra credit if you have time: as you walk, say to yourself “lifting, stepping, placing” for each movement of each foot.

Bareich ברך – blessing after the meal and drinking of the third cup of wine

Gratitude opportunity: Before or after saying the blessing after the meal, share one aspect of tonight’s seder that you are grateful for in this moment.

Hallel הלל – recital of the Hallel & drinking of the fourth cup of wine

Praise and song with nature: As we sing hallel and enjoy our 4th cup, imagine one sign of spring such as a tree bud or flower. Close your eyes and picture it celebrating the unfolding of warmth and light that comes with the new season.

Nirtzah נירצה – say "Next Year in Jerusalem!"

Turn to someone next to you or share with the entire group farewell blessings for their journey home or a sweet night’s rest.

Why Passover Yoga?

Passover is a time when we recall our ancestors’ Exodus from Mitzrayim. At the seder, we speak of the struggle of the slaves, the bondage they lived through and their journey into freedom. The Haggadah enjoins us every year to see ourselves as having been freed from Egypt ourselves. How do we do that? This yoga practice aims to take that question from the intellectual into the emotional and to ground in the physical. This practice invites us to stop and notice where we feel tightness in our bodies and a longing for freedom in our spirits.

Passover requires a lot of preparation: cleaning, cooking, and bringing all your people together. Let this yoga practice be a time to devote to your own body, spirit, and soul as a way to prepare yourself to welcome others.

OPENING MEDITATION

Find a comfortable seat. Try an easy pose like (sukhasana) or kneel in hero’s pose (virasana). Take a few moments to settle in, perhaps seating yourself on the edge of a folded blanket or block. You can also sit in a chair.

Go ahead and let your eyes close or keep a soft gaze downward. Allow your thoughts to turn inward. Feel your sitting bones underneath you. Lengthen your spine as you lift the crown of your head toward the ceiling. Notice if that gives you more space in the belly and the chest. Roll your shoulders up toward your ears and then release them down your back. As you breathe in, let your belly expand. As you exhale, empty your belly completely. For a few minutes, focus on your breath, noticing the subtle sensations in your body.

Stay here with your breath, continuing to inhale and exhale exploring your Neshama, or soul. In Hebrew we have a few different words for soul and breath. One of those words is ruach, often translated as “spirit” or “wind.” In fact, in the Exodus story, the children of Israel are described as being kotzer ruach, having shortness of breath. Check in with your breath and your spirit. How is your ruach? Your breath? How is the internal weather of your heart and mind? Without judgment, simply notice.

Take a moment to see if you notice where in your body you feel constriction, anywhere you encounter that sense of Mitzrayim. Now, see if you can simply breathe into that place.

When you’re ready, slowly begin to open your eyes. As you begin to warm up your body, you might take some simple rounding and caving of your spine, or move your body in any way that feels good. These warm ups bring some fluidity to the joints and spine, easing movement.

Opening Kavanah: You Are Sovereign

The foremost theme for this month and the gift of Passover is movement from slavery to freedom, from constriction to expansion, from reacting to the demands of others to acting from a place of internal sovereignty. Please take on these suggested poses (and those from any body-based practice) with this in mind, and keep your own body’s unique needs in mind as you practice this yoga.

Upon receiving the Torah at Sinai, the Israelites camped at the base of the mountain as a community. But each person also heard their own unique message and arrived at their own understanding of Torah and the Jewish tradition. When the Israelites received manna in the desert, the amount each wanderer received was according to their specific and individual needs — no more and no less. Remember, you are the authority and you are sovereign over the gorgeous and entirely unique domain that is your body-soulheart-spirit being, for this practice and always.

Theme 1: Moving From Constriction To Expansion

Mitzrayim

When we look at the Hebrew word Mizrayim, we see within it the word tzar, which means “constriction” joined to the word mayim, which means “water.” All of the joints in our bodies are surrounded by water in the form of synovial fluid. As you practice these poses, bring awareness to the fact that the joints (tzar) in our bodies — wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles. These enable us to move, but also need mayim. We need softness and fluidity in order to be healthy and strong.

Theme 2: Softening the Heart

"And Pharoah hardened his heart..." -Exodus 8:28

As Pharaoh witnessed and experienced the Ten Plagues, we hear over and over that his “heart is hardened.” The language in the text indicates that his obstinacy became habitual. Releasing habitual practices that no longer serve is another theme of Nissan.

Facing the burning bush, Moses is told to “take off his shoes” (Exodus 3:5). But the Hebrew can also be translated as “unlock your habits.” Day to day, as we sit and move with postures of leaning over computers and steering wheels, we create a habitual shape in the body that has our shoulders rolling forward and chest collapsing, creating a “closing of the heart.” Heart-opening poses support us in opening our hearts and shoulders, and also bring awareness to the spaces behind our hearts. They provide a counter to the habitual way we move through the world.

Theme 3: Stepping Into the Sea On Dry Land

And the Israelites entered the sea on dry land” Exodus 14:29

It’s fascinating to think that the sea parted for the Israelites. The text says the Israelites stepped onto dry land b’toch, “inside of,” the sea. How could the land be dry if the sea had just parted? Have you ever tried to walk on wet sand just after the waves receded? It’s not easy. Yet this is our task in Nissan. How can we find dry land among turbulent waters?

How can we maintain stability and connection in times of change and upheaval? How can we stay upright and connected to what’s solid during intense change?

These standing poses can help us feel our own feet solidly rooted. They allow us feel our legs rising up from that foundation as a source of strength and support as we move through the ever-changing world and reach up for our dreams.

CLOSING KAVANNAH

Breathe. Let the body and mind settle. Allow your body to begin the powerful work of healing itself by simply allowing yourself to be.

Consider what we can accomplish during this month and during our Passover experiences that will help us, our communities, and the world walk towards symbolic Jerusalem, towards a place that feels like home. The Haggadah reminds us that once we were slaves, but now we are free to move about at our own will. How are you — how are we — moving towards freedom?

The Haggadah also reminds us that not all people are free. We must free ourselves to help others to do that same. We must begin to heal ourselves and then help others heal.

May we all find peace, joy, and movement this Passover. And may we send our blessings to all who are need of freedom and healing.

--------

This activity was created by Rabbi Sarah Tasman and Julie Emden, RYT-500. Sarah is a lifecycle officiant, mikvah guide, Jewish yoga teacher, and a member of the Shechinah Council for At The Well. You can find her at www.rabbisarahtasman.com.

Julie is Director of Embodied Jewish Learning at Jewish LearningWorks in San Francisco. She offers workshops, retreats and a teacher training in Embodied Jewish Wisdom. Contact her [email protected]

For the past 5 years Yesh Tikva’s Infertility Awareness Shabbat has been a campaign that has increased and positively impacted the conversation surrounding infertility within the Jewish Community. Each year it is observed two weeks before Pesach when people are getting their minds set for Passover cleaning and preparing for family time. The Rabbis add extra “refresher courses” to ensure you are getting every crumb out of your home, schools spend WEEKS getting divrei Torah and projects ready to be sent home, but for many couples struggling with infertility, it is expected that they travel to family, since it is perceived that they don't have a lot to pack up, and can join in the sharing of ideas and projects of their nieces, nephews, cousins, etc. It may seem like this “unburdened” couple has it easy… they only have to worry about themselves, they don't have to clean their home with as much care, but in fact, this holiday ranks among the hardest of holidays to “celebrate” because of one refrain… “and you shall tell your children.”

This year, Yesh Tikva has chosen a special theme for Infertility Awareness Shabbat one to prepare us for supporting others during this holiday, and to “Hold Space” for those facing infertility. What does this new trendy statement mean?

When you hold space for someone you have intention when listening to them. However, it is not just listening, but you need to validate them and not add any of your own judgments, bias, and insights. Imagine you're holding a bucket for them, a bucket of hope, where they can put all their anger, fear, frustration, and prayers for you to hold for them and guard so they feel safe and seen. This is what holding space means.

The core of the Passover seder is the Maggid, telling over the story, which begins with “Ha Lachma Anya,” explaining the pesach offering, matzah and marror. “Whoever is hungry, let him come and eat; whoever is in need, let him come and conduct the Seder of Passover. This year we are here; next year in the land of Israel. This year we are slaves; next year we will be free people.”

The seder is an instruction manual of how to “do Passover” through inclusion. The four sons represent all types of personalities, and how you should meet people at their level to ensure the story is understood. This concept does not only apply to the four types of children, but rather for all those gathering around the seder table. The people at your table whose families are not complete fall into at least one of those categories.

See them, empathize with them, recognize that they are currently in a state of slavery, slaves to the calendar, the clock, their doctors, their medications, their cycles and how they truly dream of the day when they will be free. This year, they are in need, so take the time to look around your table, recognize what blessing you have, and acknowledge that there are those who may have their health maybe a spouse, maybe even one child, but their dream of their family unit is not complete, and therefore they are still in pain. Don’t offer “at least” comments:

“At least you can travel,”

“At least you have a husband who loves you”

“At least you have one child”

These are not helpful comments. Your job is to see them for who they are and hold that bucket for them. They may not want to fill your bucket, but they know it is there for them.

For those of you who are reading this and nodding your head, know that we, at Yesh Tikva, hear you and see you. The goal of Infertility Awareness Shabbat is not to shine a spotlight on you, but rather on our community as a whole in order to make a more inclusive, educated, understanding and sensitive Jewish community. We wish you a holiday that will enable you to feel free and hopeful throughout your journey through the desert and eventually reach the promised land soon.

--

Elie Salomon is the Fertility Advocate and Community Outreach Director and Co- Founder of Yesh Tikva. After informally counseling others through their fertility journeys, she became a founding member of the organization in 2015. Elie has become a major advocate in the infertility community by stepping forward and sharing her story so that others can understand what many cannot vocalize. A natural educator, Elie is also the Program Director at the Nefesh Yehudi Academy: After-School Judaic Studies Program in East Brunswick, NJ. She is a former Television Producer with credits on CBS, MTV, and NBC shows. Throughout her career she has interviewed celebrities, physicians and everyday people in order to research and produce informative content for the viewing public. In her own journey through infertility, she has utilized those same skills to gain vast knowledge in order to become the best advocate for her own care.

Yesh Tikva, Hebrew for “There is Hope,” was established to end the silence and create a community of support for all Jewish people facing infertility. Yesh Tikva gives a voice to these struggles, breaks down barriers and facilitates the conversation surrounding infertility. For more information visit us at www.YeshTikva.org

This Pesach, we have been invited out for dinner on the seventh night of pesach to a family who has the minhag to wear beach clothes to dinner in celebration of the anniversary of Kriyat Yam Suf.

I am loving this idea-- not only because I can not wait to wear my flippers and snorkel gear to dinner on Thursday night, but I realize it has really made me really think about the significance of the experience of kriyat Yam Suf.

Imagine the scene. The Jews have fled Egypt, leaving confusion and pandemonium behind them. And then are faced with the sea-- Did they know there was a sea there? Had they realized they were running into an insurmountable obstacle? The fear must have been astounding.

We are taught that one man, Nachshon ben Aminadav, took the ultimate leap of faith and jumped into the sea, at which point, God took over and split the sea. The Jews crossed over on dry land, walking between columns of water, between the drops.

What an interesting relationship we as humans have with the natural world, and with water in particular. Water is life giving, and we are nothing without it. Yet, too little water or too much water, for a human being or for the earth is disastrous.

It is of particular interest that we use water in our ritual cleansing, our mikveh experience. Mikveh is a transformative experience changing someone from an impure status to a pure status. It is not an external cleaning but an internal spiritual transformation.

The Jews of Egypt had to go through the water, walk between the water, to become spiritually transformed by the experience. They brought with them all their fears, hopes and the faith of Nachshon ben Aminadav.

Mikveh can be a challenging experience, depending on where you are in your feelings towards religion, God, spirituality and what is happening in your own personal life. There are times when we feel connected, and times we feel disconnected. There are times we are hopeful, times we are afraid, and times when we willingly surrender to our faith. For brides, mikveh has the connotation of faith and hope in their future. For women experiencing infertility, mikveh can be a reminder of another month gone by without conceiving. Experiencing mikveh, not knowing what the next month will bring, can be a powerful and complicated experience. One can feel hopeful in the mikveh, and one can feel loss. Tears can melt into the mikveh waters and become indistinguishable from the other droplets. The Mikveh, like Yam Suf, can absorb an individual, her faith, hope and fear in the present and the unknown future.

For my next mikveh experience, I hope to reflect on the fear that Bnei Yisrael must have felt facing the water, the hope that Nachshon had as he jumped in, and the way that the water feels surrounding all of my human emotions and experiences. Now, if only I could wear my flippers!

--

Dr. Wasserstein is a psychologist in Maryland and Virginia specializing in infertility. This selection was originally published in the Eden Center blog at http://theedencenter.com/the-waters-of-the-yam-suf/

How to Use Your Privilege

By Rabbi Avi Killip Jan 14, 2020

Parashat Shemot (Exodus 1:1-6:1)

Moses is the original social justice lobbyist. When Moses wakes up to the injustice of the Israelite slavery, he is not in a position to make any grand changes to the social and economic structures of Egypt. He is not the Pharaoh. But he is a “prince of Egypt” and that comes with some privilege and avenues for changemaking. Lobbyists use relationships to influence the decision makers in power. Shemot Rabbah, our midrashic collection on the Book of Exodus, imagines several different potential interventions from Moses to improve the lives of the oppressed.

Option One: Direct Service

In Shemot Rabbah 1:27, Moses offers direct help. The midrash tells us that when Moses saw a person struggling with an unjust burden, “he would use his shoulders to assist each one of them.” Moses is not afraid to get his hands dirty. He gets down in the mud with the slaves and tries to help. This kind of direct, one-to-one justice work is real, impactful, and potentially life-changing for individuals.

Option Two: Smalltime Resistance

Then Moses starts to think a little bigger. Perhaps he realized that the problem won’t be solved one burden at a time, and so Moses seeks a way to help more people at once. He looks for people with particularly harmful burdens and starts shifting things around, changing the job assignments to be more reasonable:

“Rabbi Eliezer the son of Rabbi Yose the Galilean said: [If] he saw a large burden on a small person and a small burden on a large person, or a man’s burden on a woman and a woman’s burden on a man, or an elderly man’s burden on a young man and a young man’s burden on an elderly man, he would leave aside his rank and go and right their burdens, and act as though he were assisting Pharaoh.” (Shemot Rabbah 1:27)

Here Moses begins to rebel as an act of resistance to Pharaoh’s tyranny. He starts to work against Pharaoh. By impersonating a task master, he claims more authority than is rightly his and is able to help more people.

Option Three: Lobbying for Systemic Change

Finally, Moses seems to change course and try a completely different tactic. Instead of helping individuals directly, or even reorganizing on a small scale, Moses seeks to make change for the entire Israelite slave population. He uses his personal relationship and access to Pharaoh to suggest a major change. In Shemot Rabbah 1:28, Moses convinces Pharaoh to allow his slaves to rest on shabbat. Like all good lobbyists, he does this by making the case that this is in Pharaoh’s best interest. He argues that well-rested slaves are healthier and therefore more productive:

“Another interpretation: “And he saw their suffering” that they did not have rest. He went and said to Pharaoh, “One who has a slave, if he does not rest one day a week, he will die! While your slaves, if you don’t allow them rest one day a week, they will die!” He [Pharaoh] said to him: “Go and do for them as you are saying.” Moses went and established the Sabbath day for them to rest.” (Shemot Rabbah 1:28)

Moses is an effective lobbyist. But lobbying will only take you so far. Sometimes what is needed is a total upending of the power structure —complete with plagues and a mass exodus! This midrash teaches us that the dual roles of lobbyist and prophet go hand in hand. Or perhaps the first is a prerequisite for the later. It is in direct response to Moses’s political actions that God decides to get involved:

“The Holy Blessed One said: You left aside your business and went to see the sorrow of Israel, and acted toward them as brothers act. I will leave aside the upper and the lower [i.e. ignore the distinction between Heaven and Earth] and talk to you. Such is it written, ”And when the Lord saw that [Moses] turned aside to see” (Exodus 3:4). The Holy Blessed One saw Moses, who left aside his business to see their burdens. Therefore, “God called unto him out of the midst of the bush” (Shemot Rabbah 1:27)

God sees how Moses notices the cries of the oppressed and gets involved. Moses is willing to stretch beyond his usual scope of power and influence to right the wrong. God is inspired to do likewise. In this version of the story, Moses is not a pawn who carries out God’s plans for liberation. Moses is the role model who gives God the idea.

How do we make change in our society? When we see something unjust, what opportunities do we have to right the wrong? We start small, and then think bigger. And when the work feels too enormous and our impact feels insignificant, we can remember Moses and ask ourselves: What might we do to invite divine intervention?

Rabbi Avi Killip serves as Vice President of Strategy and Programs at Hadar. She was ordained in 2014 from Hebrew College’s pluralistic Rabbinical School in Boston. She was a Wexner Graduate Fellow and holds a Bachelors and Masters from Brandeis University in Jewish Studies and Women & Gender Studies. She is a current Shusterman Fellow.

A couple of years ago I was out for a walk in the winter and I called my grandmother. It was one of those rare DC winter days when, as a Chicagoan, I can feel comfortable complaining about the cold - it was probably about 20 degrees. And while I’m talking to her I exclaimed a couple of times “Wow I am SO cold!!!”

And after one of the times I said it she responded “I remember being so cold,” and then shared a story about how cold she had been while living in the ghetto in Shanghai during WWII. It was so severe that she still has problems with her feet to this day.

I’ve been thinking about this since it happened. I wasn’t sure how to feel. I could react by feeling like a total jerk for complaining about the cold while I’m outside walking in my parka and boots. Or I could say ok, well this is my version of cold and that is her version of cold. But regardless, she took me out of the banality of my everyday existence and inserted her trauma into my mundane narrative.

This is one of the goals of the seder - we revisit the trauma of earlier generations. We are commanded to see ourselves as though WE left Egypt, and part of that includes slavery. We have to make ourselves feel like we were really there and it happened to us.

However, it is odd that the mishna prescribes that the core of the haggadah is the text of arami oved avi from Deuteronomy. This text describes the bikkurim festival in the land of Israel, when each farmer has to bring the first of his harvest to the beit hamikdash and say my father was a wandering Aramean, he went down to Egypt where we were slaves, God redeemed us, and now we’re free to live in the land of Israel. This selection is quite strange - after all, we have chapters about the exodus in the book of Exodus! Why wouldn’t we just use some of that to tell the story? Why do we have to go all the way to Deuteronomy? And furthermore, we are telling the story through the lens of a farmer in Israel who didn’t actually experience the exodus! You can imagine how one of the slaves who left Egypt would feel reading our haggadah. We are supposed to see ourselves as though we left Egypt, but we’re telling the story through the eyes of a farmer who got to see the fulfillment of the exodus, and never even had to experience it himself! The slave would say to him - what do you know about my story?? What do you know about what it was really like?? You have it so easy!

Many have asked the question of why this is used. Some say that the answer is as simple as - arami oved avi is a concise summary of the story of the Exodus, and so we use that as a jumping off point so we can have our own conversations. For if we were to spend the seder reading all of the exodus from Shemot we wouldn’t have time to add thoughts of our own.

There is another explanation that addresses the role of Christianity and the haggadah. The bones of the haggadah were being designed at the same time that Christianity was emerging. Early Christians saw Exodus 12 as a story about salvation, and Jesus being the paschal lamb. Rather than try to compete with this narrative or blur the lines between them, the Jews chose to use Deuteronomy instead to eliminate any possible confusion.*

Today I want to think about this question in light of the story with my grandmother. As we said, when we read the haggadah at the seder we aren’t telling the story of the exodus - we’re telling the retelling of the exodus, and this retelling is from someone who wasn’t even there. I believe this is very intentional. If the haggadah was just the story from Shemot, then every time we read it we would feel the way I did while speaking to my grandmother - wow, I can never complain. Your story will never be my story. I can never relate to what you went through, so my every day existence feels trivial in comparison. It would be paralyzing to us. By having us tell the story through the text of someone else retelling it, the haggadah teaches us that you can tell a story of trauma even if you didn’t experience it personally. That it’s OK if you didn’t suffer as much as someone else did. It doesn’t belittle your ability to participate in the story. As long as you conduct yourself with the proper humility, and you are able to really step outside yourself and into someone else’s shoes, it is your story too.

This message also goes beyond the haggadah. As we heard yesterday, there is so much suffering in the world. Children in Mali are dying by the thousands of diseases that we have long since cured. This can make us feel we are useless, that we have it so easy that it’s a joke to think we ever struggle with anything. But that kind of guilt isn’t warranted, nor is it productive. We all have a story to tell and our perspectives are all valuable. And sometimes, not having the firsthand experience is what can make you more able to help. We should always strive to understand others’ stories, and not feel guilty because we didn’t have to suffer like they did too.

-

*See Israel Jacob Yuval’s Two Nations in Your Womb pp. 79

---

Maharat Ruth Friedman is a member of the inaugural class of Yeshivat Maharat, the first institution to ordain Orthodox women as spiritual leaders and halakhic (legal) authorities. She and her husband Yoni moved to DC in 2013 to begin her position as Maharat at Ohev Sholom - The National Synagogue, where Maharat Friedman’s responsibilities include overseeing the conversion program, supervising the operation of the community mikvah, directing adult education, providing pastoral counseling, teaching in the community, and more. She is a proud member of both the Chicago and Washington Boards of Rabbis, and sits on the Executive Committee of the International Rabbinic Fellowship, of which she is also a member. Maharat Ruth is also a founding member of the Beltway VAAD. She and Yoni are the proud parents of their sons Ezra and Joebear, and their rambunctious dog, Cocoa.

This piece was originally published by Yeshivat Maharat. www.yeshivatmaharat.org